About the Book

A 17th century account of “the people that penetrate with touch.”

Engelbert Kaempfer (1651-1716) was a German physician, naturalist and explorer, best known for his travels in Persia, India and Southeast Asia in the late 17th century.

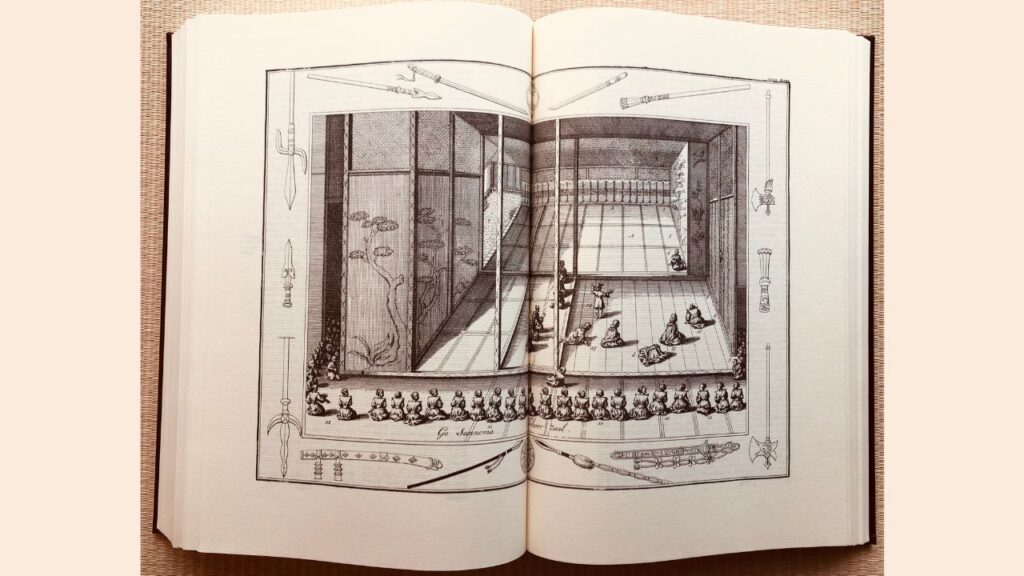

After being appointed ship’s doctor for the VOC (Dutch East India Company), he arrived in Japan in 1690 as physician for the Dutch trading post in Nagasaki and remained until October 1692. During his stay, he twice accompanied the head of the trading post on his annual visit to the Shogun in Edo.

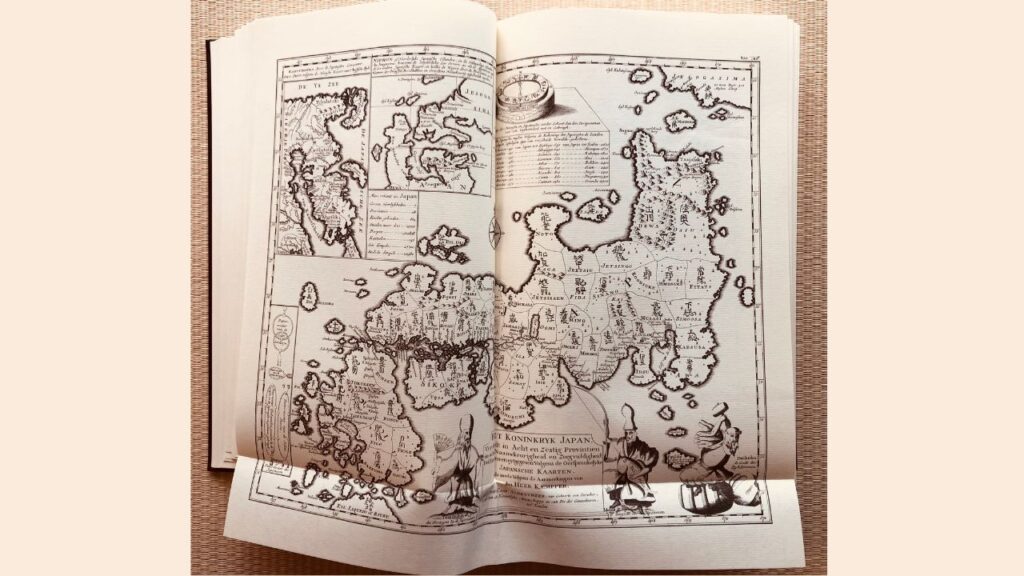

Kaempfer closely observed and documented Japan’s history, society, politics, religion and local flora and fauna. His most famous work is “The History of Japan”, which was published eleven years after his death. The book is an essential source of information on Japan’s history, culture and geography during the 17th century, and was one of the earliest Western works on Japan to be widely read and translated. It was the most comprehensive European account of Japan published, differing from previous accounts, which had largely depicted the country as an imaginary world, and is considered one of the most significant works of Japanese studies.

In addition to his contributions to natural history and geography, Kaempfer also made significant contributions to medicine. He was the first Westerner to describe the symptoms of dysentery, and he also wrote extensively on the medicinal properties of plants, particularly those found in Asia.

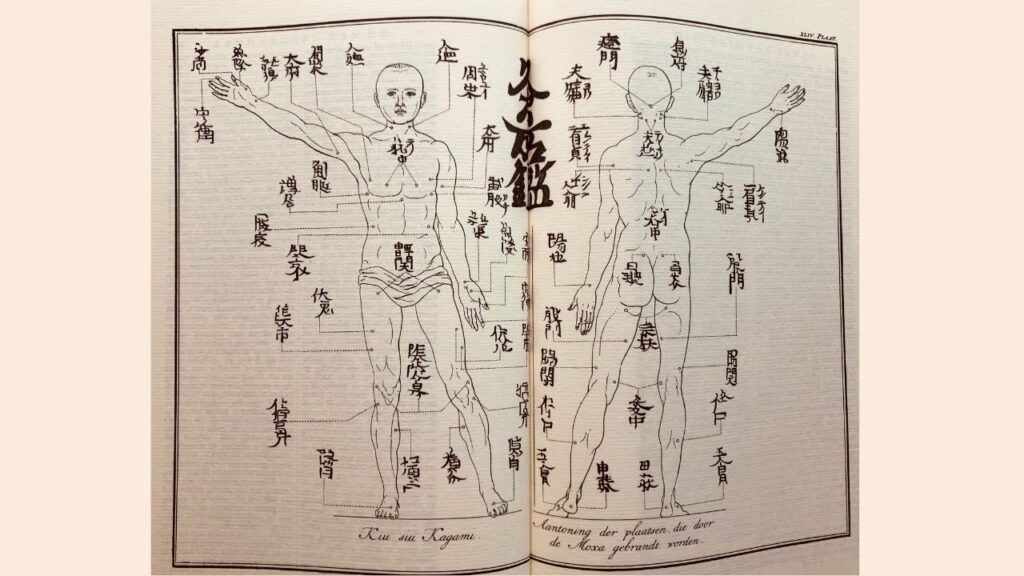

Attached to “The History of Japan” is an appendix on Moxa: “an excellent caustic of the Chinese and Japanese”, and a diagram “showing which parts of the human body are to be burnt with that plant.” Kaempfer notes the everyday use of Moxa and its purpose as both preventive and curative medicine: “The intent of burning with Moxa is either to prevent or to cure disease. But it is more particularly recommended by their physicians as a preventive medicine, for which reason they advise the healthy, more than the sick people, to make use of it.”

Regarding the practitioners themselves, he notes: “The practitioners, whose business it is to perform Moxa, are called by the Japanese Tensashi, (the people who mark the exact point) since, before applying moxa, they always feel around, and examine the part to which the moxa is to be applied.”

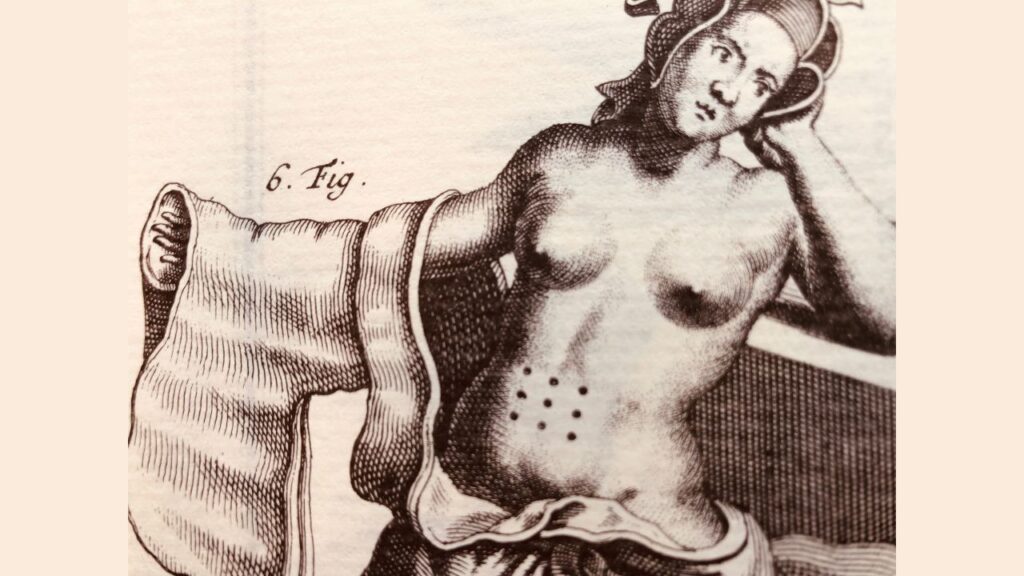

Another appendix relates to acupuncture. Here, Kaempfer’s description focuses on senki* and the stagnation of ki in the abdominal area. He also describes and depicts nine tsubos on the abdomen where this stagnation can be released. (* Senki can be translated as pain and here refers to abdominal pain, which was a very common occurrence at that time in Japan. See p. 117, “Symptoms: Kanshyoo and Senki” in Philippe Vandenabeele’s translation of Ampuku Zukai.)

Online Versions

The Royal Collection Trust: Link

Internet Archive: Link

Hathi Trust: Link

Books Google: Link

Further reading:

Kyushu university: Link

Kaempfer’s Japan: Tokugawa Culture Observed : Link